Merilyn Fairskye's sixth solo exhibition at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery.

Exhibition Dates: 8 September – 25 September 1993

"The ethical question for Lacan would be: " Have you acted in accordance with the desire inhabiting you?"

Birgit Pelzer, "The tragic desire", PARKETT 35, 1993, p.70

"But Zebul said to him, 'You see the shadows of the mountains as if they were men'."

Judges 9, The Holy Bible

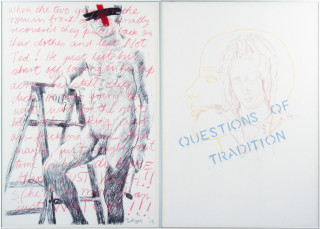

That the criminal other self may, and does, exist is a cause for anxiety. Merilyn Fairskye, in speaking of her 1990 'portraits' of the three nurses accused of murder of forty sever of their elderly patients in Vienna in 1988, suggests that they engaged " the viewer face to face with the implied morality of reading faces or looks, as deeds" (Fairskye emphasis). The ability to judge the gaze and be judged by it, continues to be a concern in this most recent body of work, though now the gaze is not returned.

In all (four) men and women who are presented before us, not one looks out to the 'real'. In what Fairskye has alluded to as a state between waking and sleeping, their closed eyes variously suggest contemplation, transcendence, self-reflection and grief. Staring into an abyss which we don't share, the four are made vulnerable. Their internal gaze figures our guilt; the mourner becomes criminal. This is no exaggeration. Fairskye has chosen here not to depict known figures of notoriety from the media archive but rather has photographed, herself the four anonymous professionals from different parts of the world. Their Polaroid images combined with first-names familiarity serves to implicate us.

For what Fairskye represents to our complicity, out non-heroic participation in and enforcement of systems of power. This is the self-monitoring subject whose gaze is one of self surveillance and who therefore becomes the epitome of Foucoult's panoptic system, if not the Catholic church . Only in this instance, Fairskye implicates the professionals and in doing also implicates our particularly Western system of knowledge. By stating nationality, and suggesting ethnicity, a shared post-colonial culpability becomes firmly located within our personal code of ethics. We have before us an (accountant, poet, lawyer and scientist) from, respectively (South Africa, Germany, Switzerland and India) - a seemingly random and otherwise nondescript selection. For their deeds they may not have won world renown, but each serves to delineate and structure the world as we understand it and for this they must be held responsible.

It is as if the realization of this malaise is written beneath their eyelids. Silenced and in silence, this eclectic grouping of professionals speak an internal dialogue of criminality and complicity. But these four faces also constitute a public staging of guilt as if heads grotesquely staked out for our scrutiny. This is also no exaggeration. It is not only the mourners who are guilty but the dead. Heads culled for public ridicule as a token and macabre threat, a media device and a judgement. Yet are these the guilty or merely martyrs? For how is this guilt constituted and in whose terms and might not the verdict be cast back at those who judge? Can there indeed be a secure point of judgement? Are we not just a culpable?

It is perhaps no accident that Fairskye's previous body of work included an image of Sigmund Freud placed in the company of various criminals including various Viennese nurses cited above. Elizabeth Grosz had drawn parallels between Einstein's conception of spatiality and temporality and the "psychoanalytic fissuring of the subject', stating that psychoanalysis necessarily implied the "seeing of all cultural production thus far (including the production of knowledge), as production from the point of view of only one type of corporeality, one type of subject (white, male, European, middle class). In effect Fairskye's collision of subjectivity with spatiality, that Grosz should also speak of the psychology of psychasthenia, that is the inability of the psychotic to physically locate him or herself, the subject's own perspective is replaced by the gaze of another for whom the subject is merely a point in space, not the focal point organizing space".

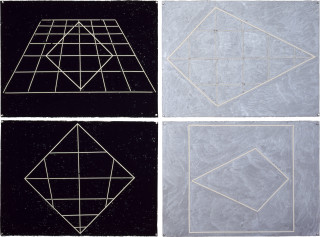

In her Proposals for rooms with columns, Fairskye precisely activates this disjuncture within a space that could be argued as between architecture and the theatre and the gallery. In each, one image of the face is cast over three or four internal, specifically created columns and fixed as a 'painting' within an installation. The image can be read in a complete form only from one point in space, thereafter with each movement, with each step it fractures. Fairskye manipulates not only the perspectival unity of the coherent subject but also that of her Proposals for rooms with columns do not all use anamorphosis, that is, distort the form from a particular viewpoint (a painters device from the Renaissance), it could be said that her imagery is similarly manipulated in that the correct viewpoint need be found before the image can be read in its coherent entirety. The strict spatiality of the image is further emphasized by its shadow, or at least that of its supporting columns, being painted on the wall behind. As Michiel Dolk has written, Fairskye's use of anamorphosis represents a feminist critique of forms of representation, drawings on those critiques which occurred within cinematic and photographic practices, practices which were strategically placed outside the painting. It is not incedental, therefore, that Fairskye's work is mediated through photography and engages installation practice. Equally of note is that element of theatricality of anamorphosis, that "peep show theatrics", which is observed by Dolk. For as becomes especially apparent in the three maquettes (which appear almost as small proscenium stages for marionettes) it is as much the viewer's role in intervening upon the space of the gallery, which activates and completes this work.

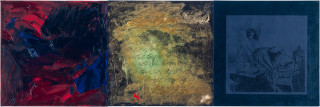

The sense of the doppelganger, as a ghostly double of a living person, figures more especially in Fairskye's Invisible Paintings, as does her use of anamorphosis. Four of the faces are painted in reverse on four small round mirrors, with the image then reflected from the corner formed by the circular shelf on which the mirror lays, to fall obliquely across the adjacent wall. In the resultant oval image, each face now appears as its positive double. Again we lose the direct clarity of the original photograph, though it could be suggested that the painting has been refracted back to us as a photographic media. This doubled image could be likened to Lacan's "imaginary body" as the subject who recognizes his or her own mirror image. Its presence could also signify "the visceral horror of one's own self image stealing one's identity", which Grosz discerns of the doppelganger in horror genre in contemporary cinema.

Both Invisible Paintings and Proposals for rooms with columns constitute a critique of essentially Western and patriarchal systems of representation, but are so in terms that refuse categorization and closure. they do not attempt to speak from a viewpoint which is beyond judgement, nor do they speak for those who they represent. Instead, they place at risk our very notion of ethics, orientating our view to an inner space or psyche which is neither 'good' nor 'evil', but which perhaps grieves at those moments of reflection and solitude between waking and sleeping, between life and death.

MICHELE HELMRICH

perspex, mirror, cell paint, shadow, light, wall

dimensions variable

Merilyn Fairskye Invisible painting (sleep)

Merilyn Fairskye Invisible painting (sleep)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1993

Merilyn Fairskye In camera

Merilyn Fairskye In camera

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1991

Merilyn Fairskye Natural Science

Merilyn Fairskye Natural Science

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1989

Merilyn Fairskye Conducting Bodies (ZORK!)

Merilyn Fairskye Conducting Bodies (ZORK!)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1988

Merilyn Fairskye Conducting Bodies (1)

Merilyn Fairskye Conducting Bodies (1)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1987

Group Show, Chaos

Group Show, Chaos

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1987

Merilyn Fairskye Figures of Speech

Merilyn Fairskye Figures of Speech

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1985