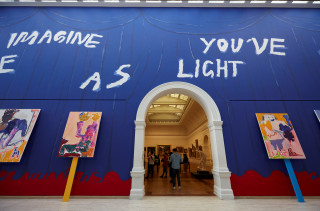

The second of three biennial survey exhibitions, The National showcases work being made across the country by artists of different generations and cultural backgrounds. Through ambitious new and commissioned projects, the 70 artists featured across three venues respond to the times in which they live, presenting observations that are provocative, political and poetic.

Exhibition Dates: 29 March – 21 July 2019

- by Justin Paton

"I think I’m more of an optimist than I am", Tom Polo is saying as I leaf through The Most Elaborate Disguise (2016), the series of 40 paintings on paper that Tom likes to refer to as drawings, and which seem, on this first look through, to indeed be winningly optimistic, with their tube-bright colours, soft bustling forms and wonky, frame-filling faces. Tom painted them in Paris where, one isn’t surprised to hear, he was also rummaging in Jean Dubuffet’s archive of art by children and self-taught artists. And what could be more childlike and playful than this head like a purple ice cream with red and green dots for eyes, or this long pink and solemn face with an arm growing from its chin, or this oddball Harlequin with polka-dot tights and a smile inside his torso?

Yet the longer I look, the more these faces and figures slip the grip of words like ‘optimistic’ and ‘childlike’. It is a matter, as in any subtle art, of phrasing and inflection – the way the maker bends and slows his images so that they say more than they first signal. There is, for a start, the way Tom softens his figures with scrubby and aerated brush strokes, so that beings who first seem boldly there are cast into states of uncertainty. Then there are the in-between colours that he spreads among his bright primaries: muddy greens, unpromising browns and pinks so pale they hardly remember red. Most tellingly, there are the little glyphs and wandering lines that Tom uses to compose his faces, marks that often seem to be on the brink of forgetting what they’re describing and turning into some other kind of notation. My favourite among the portraits renders the eyes of its subject as wobbly apostrophes or commas – a painterly punctuation that suggests the self is made, not of declarations but of openings and pauses.

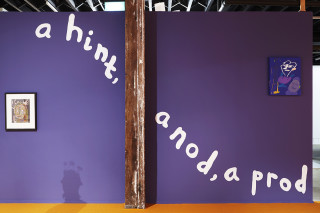

It’s not that the people in these paintings are not optimistic – just that they, like their maker, may be less optimistic than they think they are. Pensiveness, undecidedness and gentle expectancy are the feelings Tom finds in these paintings. And I love the thought that the art of painting can introduce us to states this subtle, that it can find a way of portraying the differences between how we think we are and how we are. It makes perfect sense when Tom starts talking about his affection for the commedia dell’arte, the Italian theatre of masked ‘types’ such as Harlequin and Pulcinella. Tom’s faces, broadly brushed on flat grounds and displayed on a wall that will itself be painted, do indeed resemble masks for a play, but the difference is that, in his ‘commedia’, the ‘types’ aren’t determined or known. Rather they seem blurred and emergent, as if awaiting roles in a drama yet to be written or already underway.

If these are masks, then, they are masks impressed with the hopes and mixed feelings of their wearers – repositories for the aspirations and half-formed thoughts that we entertain behind our disguises. Together they compose a portrait of how we are when we’re not sure who we’ll be – a comedy of art and life couched in the key of could and might and possibly.

Tom Polo in a part of your mind, i am you

Tom Polo in a part of your mind, i am you

Ngununggula, Bowral, New South Wales, 2025

Group Show, Under the Big Blue Sky

Group Show, Under the Big Blue Sky

Casula Powerhouse, 2025

Group Show, Works on Paper

Group Show, Works on Paper

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024-25

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Tom Polo somewhere on the edge of you

Tom Polo somewhere on the edge of you

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2023

Free/State

Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, 2022

Tom Polo linger

Tom Polo linger

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2021

Group Show, A Painting Show

Group Show, A Painting Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2020-21

Group Show, Contact Us

Group Show, Contact Us

Coment Fondu, Sydney, 2020

Tom Polo I still thought you were looking

Tom Polo I still thought you were looking

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2019

Tom Polo The National 2019: New Australian Art

Tom Polo The National 2019: New Australian Art

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2019

Group Show, Looking at me through you

Group Show, Looking at me through you

Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, 2017

Tom Polo With precious actions these vibrant outcomes

Tom Polo With precious actions these vibrant outcomes

Roche Head Office Commission, Sydney, 2017

Tom Polo What Goes on Here

Tom Polo What Goes on Here

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2016

Tom Polo But how are you otherwise

Tom Polo But how are you otherwise

Artspace, Sydney, 2015

Tom Polo GESTURES AND MISTAKES

Tom Polo GESTURES AND MISTAKES

Gertrude Contemporary, Melbourne, 2012