What is compelling about Dawson’s work is the paradox, in a slick, hi-def, 3D-printed world, of presence-in-reduction: he simultaneously pushes sculpture forward while keeping it rooted in the workshop. It is not about hiding the seams, but reveling in them.

—Dougal Phillips

Exhibition Dates: 15 November – 8 December 2018

I've got my friends in the world…

– Neil Young, "Philadelphia” (1993)

“Why are you always in Camden?” my mother asked me. I’m not. But every time I updated Facebook in Philadelphia, my post was tagged as “Near Camden, NJ.” Any proud Philadelphian will respond coldly: We certainly are not Camden.

– Josh Kruger, WHYY, March 27, 2014

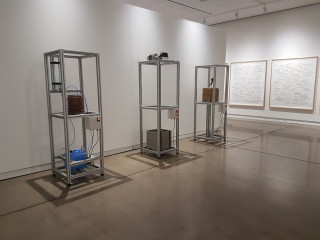

Marley Dawson is a master of assemblage and kinesis, in a kind of reverse magic. If we define magic as the power of apparently influencing events by using mysterious or supernatural forces, Dawson has, in his body of work to date, given us a revelation of a different kind: a pulling-back-of-the-curtain on transformations of objects (a painting slowly spinning; a smoke ring puffed across the air; an eternal bike skid donut; a Sisyphean brick lifted and dropped, lifted and dropped). What is compelling about Dawson’s work is the paradox, in a slick, hi-def, 3D-printed world, of presence-in-reduction: he simultaneously pushes sculpture forward while keeping it rooted in the workshop. It is not about hiding the seams, but reveling in them.

There has always been something uniquely Australian about Dawson’s practice: dirtbikes, sheds, power tools, DIY, but with ambition and scale. In this country we can build for the sake of building, and from the beginning, his practice has seemed to ask this urgent question: Why not build? We have the space, we have the tools. We have the peoplepower. What makes this Australian mission more potent, even more fascinating, is it being cross-pollinated by the artist spending an extended period living and working in the United States, in two of the most layered cities in the country, Washington, D.C and Philadelphia. The latter city, and specifically its historic 2018 Super Bowl victory, is the subject of this exhibition.

Philly pride stands alone. The proud definition-by-difference of We certainly are not Camden is notable because Camden, NJ (while in competition with places like the leadened-toxic-water-sogged Flint, MI) is anecdotally known for being the worst city in America. Separated only by a bridge from Philly and sharing a common history as anchors of the Pennsylvania Railroad, there are scale and demographic differences, but like any neighbour’s house, it throws into relief for Philadelphians that we are not them, because we are us.

The general feeling is that, about being Philadelphians, Philadelphians are fanatics. Or, to put it more correctly, Phanatics. Well-known as the greatest mascot in all of American professional sports, the story goes that a large, furry, green bipedal flightless bird with an extendable tongue fell in love with baseball forty years ago (perhaps remotely from the Galapagos Islands, his official place of origin) and became the mascot for the Philadelphia Phillies major league baseball team. But this guy is not just kissing babies and doing funny calisthenics at home plate during the seventh-inning stretch. The most-sued mascot in history (according to a 2002 Cardozo Law Review article) one newspaper report put it thusly: “The Phillie Phanatic is armed, dangerous and known to have an affinity for violence.” Recently, he shot a female fan in the face with a hot dog gun, the allegedly well-intentioned bazooka blast hitting the woman “like a ton of bricks”. In 2012, another fan filed suit when the Phanatic flung her into a pool while she was sitting on a lounge chair at her sister’s wedding. Explanations as to what the Phanatic was doing at a private wedding and how he gained the strength to deadlift a lounge chair with a human on it and hurl it into a nearby pool have been lost to the dustbin of Philly history.

Dawson knows the power of power, and the power of sports – he’s used baseball bat blanks and race tracks to stage his art. Which brings us, in very Philly fashion, from art (represented, say, by the excellent Philadelphia Museum of Art) right back to sports (represented, say, by Rocky Balboa triumphantly ascending the seventy-two stone steps that run up to the Museum). It also brings us back to birds: the Philadelphia Eagles (or “Iggles” in the local tongue) NFL team. The stadium of the team that was once clad in Kelly Green and now in a more sinister Midnight Green has been nicknamed the Nest of Death, and its devout fanbase has been described in moralizing terms as having a “long history of despicable behaviour” (a fan once punched a police horse). In 1968, fed-up fans of a hapless team stuck in a snow-covered stadium pelted snowballs (iceballs, really) at a teenager dressed up as Santa, carrying a sack full of damp towels (the booked Santa was stranded in snowbound transportation). “They’re not just booing Santa Claus;” he later reflected, “they’re booing everything.” In the mid-90s, the volume of fan ‘incidents’ was so great that a group of local councilmen set up a courtroom inside the stadium to swiftly deal with offenders. This boisterous following had, until this year, not been matched by on-field success.

February 5, 2018. The 52nd Super Bowl: Philadelphia Eagles 41 – New England Patriots 33. A relentless game, narrative-rich: five-time champion Pats and the ageless Quarterback Tom Brady going against an Eagles team led by the backup QB Nick Foles, who two summers previous had contemplated moving on from pro football (this hard-luck tale just makes him more Philly’s guy). The highest-scoring title game since 1995; yardage records smashed; first Super Bowl title ever, first NFL championship in 58 years. “Not so much a difference in quality as a difference in nerve”, the commentary went. An iconic game for NFL, sure, but for the city? Well, asked what the title meant to the city of Philadelphia, Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie said, “If there’s a word, (it’s) called ‘everything’.”

After the win, chaotic joy was unleashed. The City authorities thought they were ready for Philly sports fans’ infamous penchant for public shows of emotion – they greased the light poles to try to stop climbers. WE DON’T WANT YOU TO ASCEND was the message laid out in thick goops of Crisco cooking grease. But who’s gonna stop Balboa going up those steps? “Philly’s post-Super Bowl ‘celebration’ was really a riot” one headline stated, but ‘A rose is a rose is a rose’, as Gertrude Stein once said. It is what it is.[1] One bystander remarked to the Philadelphia Inquirer “It seems to be under control in that the city hasn’t burned to the ground yet. I think they’re handling it pretty well.” The report goes as follows: Department store windows smashed. Ritz-Carlton Hotel awning collapses with more than a dozen people on it. Cars flipped over. Cars set ablaze. Three people fell to the ground from light poles and lost consciousness. One Eagles fan could be seen eating horse manure off a street as a crowd of people gathered around him to cheer him on. People yelling “Everything is free,” while looting a Sunoco gas station. “Damn it, Philly we are better than this” said one tweet. Maybe it should have said: Philly, we are this. And Everything Can Be Free.

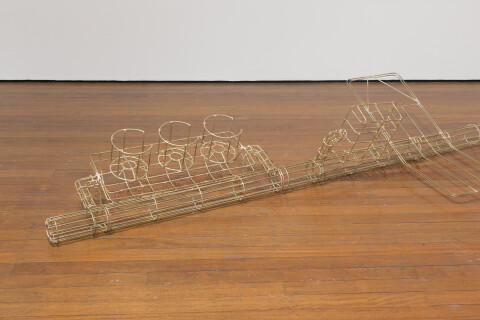

Dawson has taken the symbols of this uprising and rendered them as ghostly outlines and woven memories of this fevered time. For the Crisco grease barrel, Dawson removes the corporate image plane of the drum and shows a memorial skeleton, vestigial, emptied out not only of its goo but of quotidian signifiers, and elevated to a monument, albeit a fallen one, like a dead cannon in the now-flowering fields outside Paaschendale in West Flanders. We see a fallen traffic light, maybe the city’s most basic machine of the control of movement of its citizens – WE WILL TELL YOU WHEN TO GO AND WHEN TO STOP. Fittingly, Dawson the master woodworker fells it like a tree. It is said that because trees existed in pre-historic times eons before the evolution of bacteria that eats wood and thus rots it, fallen trees would pile up and up all over the globe, never decaying. Maybe one day, all traffic lights will look like this.

Fuck Tom Brady. To understand this game, you have to understand the teams. If the New England Patriots were a person, they would be a Koch Brother wearing a Darth Vader helmet. They are the evil empire, with their relentless master Head Coach Bellichek, their history of spying and deflating footballs – anything for a competitive edge – their Trump-buddy owner, and their QB, possibly the best ever, and getting better with every robotic year. Tom Brady is so insane about his performance that his trademarked TB12 diet means he doesn’t eat nightshade vegetables such as peppers, tomatoes, and eggplants, lest they detract for some spurious reason from his pure physical peak. When he treats himself to a dessert, it is mashed avocado “icecream”. The Philly Cheesesteak, the dish bestowed with the name of the city at the heart of the American Revolution, the birthplace of the Declaration of Independence, is a signature mix of beef and artificial cheese slop, onions optional. Trump won Pennsylvania in 2016, sealing victory, but Philly voted 6-to-1 for his opponent. The city refuses to rest.

Terry Smith once told me in the 1990s that the moment he knew Manhattan (Philly’s number one Big Brother, casting a long shadow) had changed was when the flowerbeds appeared on the streets. In the Super Bowl celebrations, Philly’s urban planter pots were tipped over, dirt spilled onto the streets. Seen here as Dawson’s sculptures, they remind us of a dark cousin to New York’s new $200 million public artwork The Vessel, which takes a similar form, and is 154 flights of stairs to nowhere. Pure aesthetic, nestled in the shiny new spectacular late-capitalism of the Hudson Yards development, if you rise to the top you will either look at the glassy facades of law firms and investment banks, hiding the older city to the east, or turn the other way to look west across the Hudson at New Jersey, far enough to appear as a hazy non-threatening expanse. But keep going in that general direction, turn south and you find Camden, then cross the bridge and there, as always, is Philly. Dawson has spoken about a haunting being ever-present in Philly: an on-edge sense that something bad is about to happen in the City of Brotherly Love (as Neil Young sang it in his own haunting voice). This is always going to be the way when you have the singular mix of American pain and American joy in one place. Insane civic pride can erupt, but the hoarse cheers settle and rest, for years, to quiet, as one great American poet (The Boss) noted in The Streets of Philadelphia: At night I could hear the blood in my veins, it was just as black and whispering as the rain.

—Dougal Phillips

[1] Credit should, however, be given to the sub-headline’s postulation that “If the crowd were majority black, the world would’ve responded very differently”.

—

Marley Dawson has exhibited extensively in Australia and has presented work internationally in group exhibitions in Paris, Hong Kong and the USA. They include Bowerbird: Clinton Bradley and the Art of Collecting, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo (2018); Future Eaters, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne (2017); Gravity (and Wonder); Penrith Regional Gallery, NSW (2016); Mine Moonlight, Museum of American Glass, Millville, New Jersey, USA (2016); Counter Compositions Artbank, Sydney (2016); We Pain, Lump - Project space, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA (2015); Solid State, Casula Powerhouse, Sydney (2015); FLEX, Flex Projects, Washington DC, USA (2013); Seven Points (part one), Embassy of Australia, Washington DC, USA (2013), and Redlands Westpac Art Prize, National Art School, Sydney (2012).

Dawson’s solo exhibitions include Explosion/Resolution, Julio Fine Arts Gallery, Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, USA (2014); Statics and Dynamics, Hemphill, Washington DC, USA (2014); Big Feelings (going nowhere), Hillyer Art Space, Washington DC, USA (2013); Purliey, Awesome Arts Festival, Perth (2009) and ECR (with Christopher Hanrahan), Performance Space, Sydney (2008).

Dawson has also participated in several commission projects such as Construction (Barangaroo), Barangaroo, Sydney (2016); Construction (T Street NW), 5x5 Public Art Project, Washington DC, USA (2014) and MCR (with Christopher Hanrahan), Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart (2011).

Public Furniture is Marley Dawson’s fifth solo show at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

102 x 152 x 4 cm

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

102 x 152 x 4 cm

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

102 x 152 x 4 cm

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

102 x 152 x 4 cm

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

102 x 152 x 4 cm

cotton/rayon digital tapestry, maple stretcher, stainless steel frame

152 x 102 x 4 cm

brass, silver solder and light bulb

303 x 70 x 120 cm

brass, silver solder and light bulb

303 x 70 x 120 cm

Marley Dawson Fizzy Drinks / Material Links

Marley Dawson Fizzy Drinks / Material Links

Kids Gallery, MAMA, 2025

Marley Dawson loose ends

Marley Dawson loose ends

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Marley Dawson Bungambrawatha

Marley Dawson Bungambrawatha

Albury City, New South Wales, 2023

Marley Dawson Plateau

Marley Dawson Plateau

Hyphen – Wodonga Library Gallery, 2022

Marley Dawson hum

Marley Dawson hum

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2021

Marley Dawson ghosts

Marley Dawson ghosts

The Phillip's Collection, 2021

Marley Dawson Public Furniture

Marley Dawson Public Furniture

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2018

Group Show, State of Play

Group Show, State of Play

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2017

Group Show, Future Eaters

Group Show, Future Eaters

Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2017

Group Show, Gravity (and Wonder)

Group Show, Gravity (and Wonder)

Penrith Regional Gallery, 2016

Marley Dawson Construction (Barangaroo 2016)

Marley Dawson Construction (Barangaroo 2016)

Barangaroo Sculpture Walk, Sydney, 2016

Marley Dawson Palethorp

Marley Dawson Palethorp

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2016

Group Show, Solid State

Group Show, Solid State

Casula Powerhouse, 2015

Group Show, Cars = my automolove

Group Show, Cars = my automolove

Caboolture Regional Art Gallery, 2014-15

Group Show, Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalists

Group Show, Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalists

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, 2014

Marley Dawson Statics and Dynamics

Hemphill, Washington DC, 2014

Group Show, Dawson, Griggs, Moore

Group Show, Dawson, Griggs, Moore

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2013

Marley Dawson

Marley Dawson

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2013

Marley Dawson Big Feelings Going Nowhere, 2013

Marley Dawson Big Feelings Going Nowhere, 2013

Hillyer Art Space, 2013

Group Show, SEXES

Performance Space, Sydney, 2012

Marley Dawson HEAVY INDUSTRY / LIGHT COMMERCIAL

Marley Dawson HEAVY INDUSTRY / LIGHT COMMERCIAL

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2011

Group Show, Purlieu

Group Show, Purlieu

Awesome Arts Festival, Perth, 2010

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2009-10

Marley Dawson Box of Birds

Marley Dawson Box of Birds

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2009

Marley Dawson Trick Shop

Locksmith Project Space, Sydney, 2009

Marley Dawson Shed

Chalk Horse, Sydney, 2008

Group Show, OBLIVION PAVILION

Group Show, OBLIVION PAVILION

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2008

Group Show, ECR

Parramatta City Raceway, Sydney, 2008

Group Show, Oblivion Pavilion

Group Show, Oblivion Pavilion

Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, Melbourne, 2008

Group Show, She's not Structural

Sydney College of the Arts, Sydney, 2007