Julie Brown is the thief of Munch, perhaps even the sodomizer of Munch. She breaks the links in the symbolic chain which govern social relations, troubles the rhetoric of stereotyped roles, which along with commodities and language, stockpile power in order to ensure the continued subordination of women in the world.

—George Alexander

1. THERE IS NO PHOENISH

She begins with dreams of rebirth. On one wall, the young-old face of a foetus is sprinkled with ash; on the opposing wall, a self-portrait burns in an amoeboid shape, catching the lips, eyes, reducing the face - fat, bone, tissue - to an acrid smoke for the existentialist gods to smoke. Life forms created in ash. The fire leaping out of the womb to complete some treaty with the stars. Julie Brown's installation, Phoenix, in Perspecta 83.

2. THE BACHELOR-MACHINE AND THE RIDDLE OF THE SPHYNX

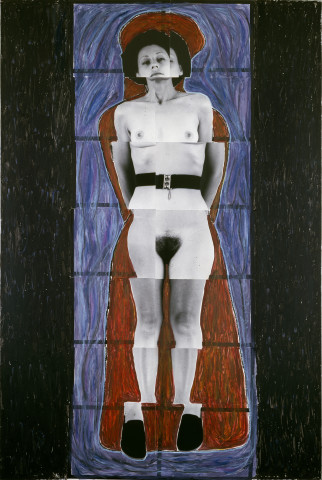

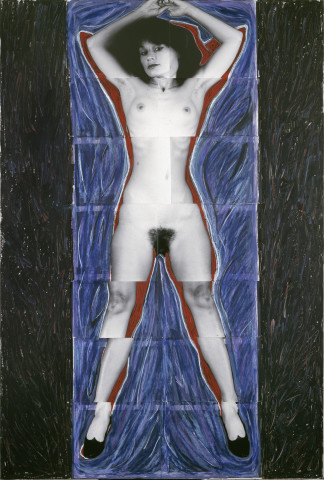

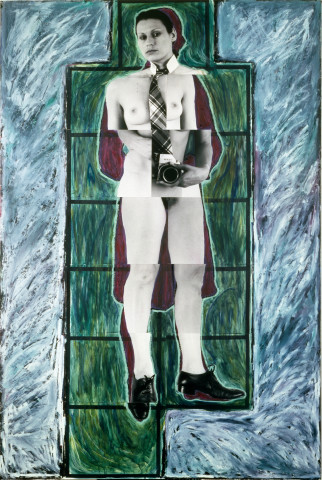

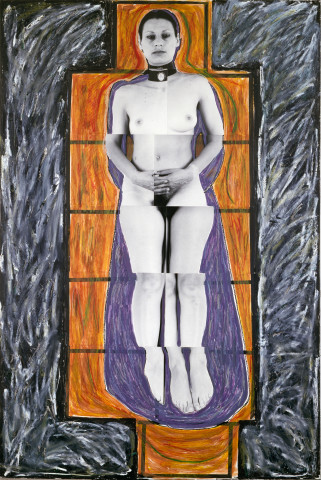

Edvard Munch, forerunner of expressionism, propagandist of the silent scream, and the silent space between man and woman, sets the meditation for these nine panels, entitled Persona and Shadow.

Munch inhabited an agoraphobic world of sick children and syphilitic mothers, where light poured into Norwegian fjords like blood from a butcher's pail. For the bachelor-machine of Munch, the lifeforce took the form of sexually aggressive femininity. Woman as vampire, as trap, as wound-gateway to death, framed in warping, buckling colours smeared on with a spatula.

Virgin-Mother-Whore: these are the classical codes of the social order that women are made to disappear into; the fantasy blueprint for sanctifying, pacifying and conquering what has always been seen as a threat to the future of the patriarchal cycle of Father-Son-Capital.

Julie Brown is the thief of Munch, perhaps even the sodomizer of Munch. She breaks the links in the symbolic chain which govern social relations, troubles the rhetoric of stereotyped roles, which along with commodities and language, stockpile power in order to ensure the continued subordination of women in the world.

3. NOT JUST A PRETTY INTERFACE

In the postmodern condition we are steeped in quotation. Authority is constituted by citation alone. Books are read as if they had already been read before. New coats of paint, hardly dry, shine in the artificial daylight of the Museum before another coat is added:

a Zeit for sore eyes.

And codes cast long shadows upon bodies. The body dealt with here is no longer the body of the expressionist or the self-victimising body-artist of the 70's. Rather it is the history of the body through the language of painting; the body with its full weight of culture, which determines its adequacy to the code.

What interests us in Persona and Shadow are the interferences - the interface hostilities between the body and its models, the personal and the political, painting and photography, male and female, hunter

and prey, the gaze and the touch.

Between the cultural heroes of Western Art and Julie Brown there is a perverse encounter of reflection and repetition; a stand-off between performance and criticism.

4. A TALKING CURE FOR THE COMMON CODE

Refracted through Munch, Gauguin, the Pieta etc, these works become an occasion for jumping out of her own self, relinquishing the subjective ego without depth, and participating - as internalised audience - in an erotic violence of stereotypes which requires Cinderella to fit the glass slipper of the male artist's codes. She finds herself enclosed in a frame from which she escapes through the Other which brings her back.

In Persona and Shadow Julie Brown travels the empty space between the cultural mannequins each bearing her mask - not as a negotiation for her "real self' behind the masks, as with the body-artists of the 70's, but like Cindy Sherman, as a consummation of her

identity as she plays the ritualistic game of possession and dispossession. You lose your identity to find it among others, a transindividual body.

Over the last hundred years in the West the body has been understood through a series of overlapping codes. In religion, aspiring to resurrection, the bottom line was the animal body; in medicine, fighting illness, the ideal limit is the cadaver, in industrial society the body model is the robot; in the political economy of signs the ideal limit is the mannequin.

In these panels the body is the radical alternative to these references, their "inverse virtuality" (Jean Baudrillard) and they become a crossroads in the current debate on postmodern sexuality and the politics of representation. (pace the recent Biennale forum chaired by Mick Carter, with Adrian Martin, Ted Colless, Anna Oppermann and their audience).

5. THE ILLUSION OF SEXUALITY AND THE SEXUALITY OF ILLUSION

Postmodernism sees sexuality as an optical illusion, part of a social irony that sees "masculinity" and "femininity" as strategies contrived by either gender. There are as many sexualities as there as sexed individuals, I've said as much myself.

And yet there are specific ways we invest in our bodies, as an emerging organisation of signs, the way we stage it and hypercathect onto codes. This is not to reassert ideology into these postpolitical times, nor assume the hustle of an outdated moralism, rather it is

a pretext for seeing the way we get hamsandwiched between the anachronism of insistent codes of patriarchy and the breathless aheadofness of a post-post-everything world.

Julie Brown explores the in-between space. Not just claiming a difference where human folk come in two categories - with or without a penis - but in the superimpositions, the overlay, ambiguous quotations that maps the specific region between individual bodies. The connections and differences that make up sadism, masochism, tenderness, obsession, fertility, passivity, sensitivity, jealousy. In every relationship one or other is the Other writes Mary Fallon, one or other is a liar, is to blame, has their hands on fire, sucks their thumb, is destroyed, has no name.

Politics sets up distinctions - male/female, East/West- then builds itself upon it, like the Berlin Wall, in order to extend the domain of one over the other by a policy of ideological expansion.

The artwork allows the body to disarticulate and rearticulate according to the pathways of desire catching us between the illusions of sexuality and the sexuality of illusion.

6. CLOSURE AND DISCLOSURES

Edvard Munch attempted to codify the excess of women with the gravitational field of classical codes and archetypes, underwritten by biological economic, libidinal values constructed for them. Men fear women because their pleasure is an enigma, try as they may to find the technical means to produce it in a predictable and guaranteed fashion: vibrator, clitoris, G-spot.

The woman's body is a topology of erotic potentialities. Its geography is much more diversified, having sexes all over, escaping the regrouping in the frame of the male. Note in Persona and Shadow the amputations and proliferation of legs, feet, breasts, hands creating new sexual doublings, surrogate penises, erotic conjunctions that traverse the mosaic of photographers like a tidal drift.

The erotic imagination never creates fully developed situations, things happen in fragments. Munch's frame is like a male mirror, phallically marking and reflecting what it encloses. Julie Brown has already played a few games with that mirror. In Disclosures (I.C.A. Central Street, 1982) the mirror and camera play the game of representation, transferring us to the space of the Other. Projecting the visible, not as a window onto the world, but into a non-space or fictional space, making of representation a vertigo. The visible gets redoubled, is present only as a sign of its absence. In Disclosures, through left and right, front and back, image and meaning are turned inside out.

For the photographer or painter the visible is always double - a duplication, a redoubling of the image. In Persona and Shadow Munch's painting of imaginary women is the first double of the visible. Julie Brown redoubles his forms and colours. She plays second fiddle, like Echo - the goddess of postmodernism - who never talks first, never invents her own discourse, cannot refuse a response and repeats the ends of phrases she can never begin. She speaks as the male speaks, evades as the male evades, play acts life as men play act it. The she does the switch.

7. TEXTS: THE VOICES-OFF OF CULTURE.

The texts that accompany Persona and Shadow are nine broken off fragments like the voices that accompany us and angle our relation to the world. Spaced out they make a constellation of themes: sexual difference, with woman-as-daemon or excess; loss of identification through over-identification and the role of persona or mask; the gaze of the male voyeur, sadist, analyst; nakedness and vulnerability; death-in-life and death-in-love. And crucially, the sexualisation of space: inhabiting the 3-Dimensional world of masculinity is the flat-space, the double dimension of femininity.

8. THE GAZE, TOUCH AND THE ART OF FLOATATION.

The work is not content to describe: it remakes the object, breaks it down in the urgency of process. The grid or mosaic of photographs are an internal mapping that play out the ambiguities of perception. In remaking Munch she escapes the magnetic field of

his coffin-like frames. As patriarchy cannot contain the overflow of a woman's productions (Luce lragaray), she floats in a 2-D space that is yet plural tactile, multiple.

That dis-location through the lattice of photos that make up the body inside the Munchian silhouette, make us puzzle through different perspectives: naked/ dressed, empty /filled in, present/ absent. Dressed by society the woman is naked for all the world (not) to see.

These cibachromes subvert the sexual economy of the centrefold through this complex art of floatation. Why? Because the woman takes her pleasure from the touch more than the gaze. Desire creates the body in fragments, like a broken statue whose parts - torso, arms, legs, head or belly we find or see in turn as separate objects. The body is dissected as if its real existence is being constantly questioned and requires constant proof. It is the erotic space of touch that makes them exist for her. The two dimensions are that of touch. The gaze is 3-D.

9. THE GOLDFINGER GIRL AND THE CIBA-BODY.

The centrefold nude is hyperreal - exposed to the very pores, without the hide-and-seek, the puzzle of foreground and background of the 2-D floatation in the gridded photos. The limit instance of the centrefold is the James Bond Goldfinger girl: becoming a corpse at the same time as becoming a gold-standard hard-on.

The cibachrome is a second skin, a transparent film that vitrifies the body. It opposes the porous, the permeable, the metabolic body. The ciba-body neither absorbs nor exudes, is neither impastoed nor smooth. The ciba is a lake, a film, iced skin,cellophane, with all the qualities of closure.

And yet its lamination has a depth, is true and false involves us in the drama of seduction and violation'. The 3-D space of Munch is being replaced by the 2-D space of the photographs.

Colour breaks the skin like a wound, summons pain - the pain of man, the pain of woman. If Munch feared death, feared women, Julie Brown watches her prey closely, shadows it intimately. With remote mineral calm, in auras of colour, his brushstrokes become hers. She is the death of what she watches. The projection meets its double at the threshold of the furnace door on the other side of the cibachrome. What is most desired melts fastest.

Has woman become the ghost of man made visible?

Or vice versa?

— GEORGE ALEXANDER, MAY 1984.

Group Show, Dreamz

Group Show, Dreamz

Sydney College of the Arts, 2025

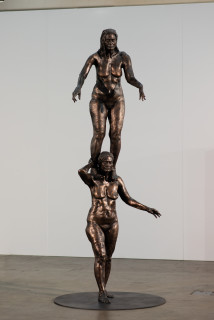

Julie Rrap Carapace

Julie Rrap Carapace

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Julie Rrap Past Continuous

Julie Rrap Past Continuous

Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia, 2024-25

Julie Rrap SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders)

Julie Rrap SOMOS (Standing On My Own Shoulders)

Melbourne Art Foundation Commission, 2024

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Julie Rrap The Dust of History

Julie Rrap The Dust of History

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2022

Free/State

Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, 2022

Julie Rrap Blow Back

Julie Rrap Blow Back

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2018

Julie Rrap Remaking The World

Julie Rrap Remaking The World

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2016

Julie Rrap Remaking The World

Julie Rrap Remaking The World

Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2015

Julie Rrap Loaded

Julie Rrap Loaded

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2012

Group Show, Head On Photography Festival

Group Show, Head On Photography Festival

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2011

Julie Rrap 360 degree Self-Portrait

Julie Rrap 360 degree Self-Portrait

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2010

Julie Rrap Escape Artist: Castaway

Julie Rrap Escape Artist: Castaway

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2009

Group Show, Lucky Town

Group Show, Lucky Town

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2008-09

Julie Rrap Bust(ed)

16th Biennale of Sydney, 2008

Group Show, Summer '07 '08

Group Show, Summer '07 '08

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2007

Julie Rrap Body Double

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2007-08

Julie Rrap Body Double

3rd Auckland Triennial, 2007

Group Show, STOLEN RITUAL

Group Show, STOLEN RITUAL

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2006-07

Julie Rrap Fall Out

Julie Rrap Fall Out

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2006

Julie Rrap Soft Targets

Julie Rrap Soft Targets

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2004

Julie Rrap Fleshed Out

Julie Rrap Fleshed Out

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2002

Group Show, The First 20 Years

Group Show, The First 20 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2002

Julie Rrap A-R-MOUR

Julie Rrap A-R-MOUR

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2000

Group Show, All Stars

Group Show, All Stars

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2000

Julie Rrap Porous Bodies

Julie Rrap Porous Bodies

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1999

Julie Rrap

Julie Rrap

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1997

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1997

Julie Rrap Work 1993-1996

Julie Rrap Work 1993-1996

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1996

Group Show, Stockroom

Group Show, Stockroom

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1995

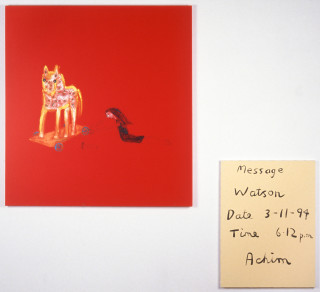

Group Show, Photosynthesis

Group Show, Photosynthesis

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1994

Julie Rrap Persona and Shadow

Julie Rrap Persona and Shadow

Online Gallery, 1984

Julie Rrap Persona and Shadow

Julie Rrap Persona and Shadow

Online Gallery, 1984

Julie Rrap Myth and Memory: The Eclectic Dream

Julie Rrap Myth and Memory: The Eclectic Dream

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1983