In 1984 the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York presented Australian Visions, an exhibition surveying Australian contemporary art, featuring RO9 artists at the time Dale Frank, Jan Murray, John Nixon, Mandy Martin and Vivienne Shark LeWitt. Curated by Diane Waldman.

Exhibition Dates: 25 September – 25 November 1984

Impressions of Australia

For the first-time visitor to Australia the initial impression is the overwhelming presence of the land. The vast open terrain, although tamed in the cities, is unruly in the bush and the outback, and the feeling of it is all-pervasive. So too is the immense sky which sits low on the horizon and provides a spectacular and ever changing panorama. The lush, fertile Pacific coast and the awesome rich red desert, the heat and the intensity of the light which enhances even the whitest white, the most brilliant purple or yellow, the graceful plumed birds, the ungainly, winsome animals, the eucalyptus and the ghost gum trees impress themselves indelibly on the senses in a continent full of dramatic and unexpected contrasts.

Australia has often been described as the "last frontier" and, indeed, the challenge and promise it offers lends credence to that appellation. For Europeans and Americans, Australia today still represents the romantic ideal, the dream of the paradise regained that Erasmus Darwin responded to when he first sailed into Botany Bay in 1789:

Where Sydney Cove her lucid bosom swells,

Courts her young navies, and the storm repels;

High on a rock amid the troubled air

HOPE stood sublime, and wav'd her golden hair... [1]

Whereas aboriginal Australia is thought to have been settled some 40,000 years ago, European Australia was based upon a series of convict settlements founded in the eighteenth century. When, on January 18, 1788, _a fleet of eleven ships commanded by Captain Arthur Phillip, who became the first Governor of the colony of New South Wales, reached Botany Bay over 700 of those on board were convicts. By 1840 nearly 100,000 convicts had been sent from Britain to the mainland of Australia. Although free settlers brought the population to 400,000 in 1850 convicts were transported to Tasmania until 1853 and to Western Australia from 1850 to 1856 to compensate for a serious shortage of labor. [2] The continent consisted of territories that were granted independence individually at various times; only in 1901 were the colonies federated as states to become the Commonwealth of Australia.

Despite these grim, hard beginnings, Australia became a prosperous land, developing a wool industry and a farm economy. It became as well a pioneer in social reform national suffrage for women was achieved with federation in 1901 - and a society whose pioneer stock, largely English and Irish, has been strengthened and enriched by an influx of Europeans of other origins and Asians. Although Australia will shortly celebrate its two hundredth anniversary, it remains a nation that came into being in the postindustrial era. A land mass just slightly smaller than our own, Australia is populated by only about fifteen million people. It is thus still very much a nation that is becoming- in its political, economic, social and cultural identity. It is this sense of becoming, of newness, of raw energy and vitality that infuses the land, the people and the art.

From its beginnings, Australia had much in common with the United States. Both were peopled largely by outcasts from Europe; as pioneers in a new land their lives were harrowing struggles for survival. They had in common traditions determined, at least in part, by their origins as British colonies. And both regarded and recorded their new landscapes with a mixture of awe and curiosity. Although Australia produced no equivalent of the Hudson River School, which emerged here in the 1820s, the German- born Eugene von Guerard, who settled in Australia in the early 1850s, reveals affinities with American nineteenth- century romantic landscape painters. Like many of the artists of the Hudson River School, von Guerard studied at the Dusseldorf Academy in Germany. Like them, he presents in his work both the majesty of nature and the fury of its forces. Although von Guerard long enjoyed acclaim in Australia, his art fell out of favor there during his lifetime. A form of naturalistic plein-air painting, similar to that of the Barbizon School popular in France, soon became the leading fashion in Australia during the late nineteenth century. However, von Guerard and other nineteenth-century figures left a meaningful legacy in initiating a landscape tradition that has prevailed throughout~ much of Australia's brief art-history. To be sure, that tradition was interrupted during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s when painters, with few exceptions, looked to Europe an particularly to America for artistic models.

Despite forays into abstraction during the postwar era, little in modern Australian art rivals the sophisticated inventions of such avant-garde Americans of the early twentieth century as Auther Dove, Georgia O'Keeffe, Stanton MacDonald-Wright or Patrick Henry Bruce. More important, Australian artists have never approached the profundity of the American commitment to abstraction, as expressed by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Clyfford Still and other masters of the New York School. Yet Australians have made a unique contribution by developing an art inspired by the landscape and the figure which could have remained a merely regional idiom - as it did in the United States between the two world wars-into an authentic and powerful pictorial style.

Australia's artistic coming of age has resulted from an acknowledgement of the continent's isolation from the Western hemisphere. The isolation that in the past has engendered a deep sense of insecurity today gives rise to a growing recognition on the part of many Australians that they have a special role to play in the world. Thus, the current resurgence of figurative and landscape painting in Australia can be attributed to a new awareness of and pride in a native tradition rather than to the influence from abroad of Nee-Expressionism. Many younger artists working today have turned for inspiration to exemplary figures who came to prominence in the 1940s, such as Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Arthur Boyd and John Perceval and to more recent painters such as Jan Senbergs. By revivifying their traditions, the younger Australians are able to make an original contribution to the ongoing international dialogue on art, an Unheralded, singleminded contribution that is marked by immediacy and a sense of promise.

Australian art in the 1970s, prior to this resurgence, was very much like the art in major centers throughout Europe and the United States: conceptual art, video and performance predominated where painting and sculpture had previously held sway. Although little of lasting value emerged during the decade, Australian art of those years already was informed by special qualities that set it apart and lent it credibility. The subtleties and nuances, the emotional distancing of an art form that is about art-the predominant international expression of the 1970s - were absent from Australian work of that period. Instead, there was a brooding, introspective mood, a sense of urgency and drama and an intense, hothouse palette-hallmarks oi much of !he very different art of the 1980s in Australia.

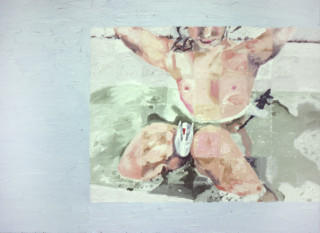

We see in the young Australian art of today a directness, a powerful emotive sensibility that finds expression an intense pathos or humor, a sense of melodrama a raw energy, a rude sense of color and form and finally an awkwardness that is both uncomfortable and reassuring in its vitality and affirmation of feeling. Recent Australian art is disquieting because, like Australia itself, it directly confronts our consciousness. It refuses to be polite and quiet. It refuses to draw upon pop imagery we can consume and forget like supermarket products. Art in Australia, because it is ungainly and demanding does not conform to our expectations of a seemly art. It asks of us rather than simply gives to us. To this extent it is unyielding and unsympathetic and distinct from the humanist landscape and portrait painting that has evolved since the Renaissance. It also strands out of the tradition of social realism in that it speaks more intensely of individual inner feelings than of the issues of the day. The paintings of Peter Booth, Dale Frank, Mandy Martin, Jan Murray, Susan Norrie, Vivienne Shark LeWitt, the photographs of Bill Henson, the installations of John Nixon are deeply even obsessively autobiographical in nature yet they are also meaningful in what they say about Australia and about the state of art today.

Australia today is a curious amalgam, a postindustrial society superimposed upon a wilderness. It is poised close to Asia but still rooted in European tradition. It benefits from its distance from the West in its independence but suffers from the absence of first hand information. Change is swift yet many are wary of moving too quickly into the future. Australian suffer from a certain collective neurosis based upon their isolation and their love, fear and dread of the land. Now more frequently than before, critics of the arts are Australia's cultural identity.

Curiously, this visitor found that the artists themselves are relatively undisturbed by this sense of dilemma. They welcome the may visitors increasing curiosity about their work and seem willing and eager to see it tested on an international scale. The boldness and individuality of current Australian art mirrors the boundless vitality and variety of an Australian Society in rapid flux, poised on the threshold of a new era.

— Diane Waldman

[1] Erasmus Darwin, "Visit of Hope" from The Voyage of Governor Philip to Botany Bay, 1789, reprinted in Ian Turner, ed. The Australian Dream, New Zealand and Melbourne, 1968, p. 2.

[2] Bill Hill, ed., Australia Handbook 1983-1984, Canberra 1983, pp. 14-15.

Group Show, Relic

Fairfield City Museum & Gallery, 2025-26

Group Show, Good as Gold

Group Show, Good as Gold

Rockhampton Museum of Art, 2025-26

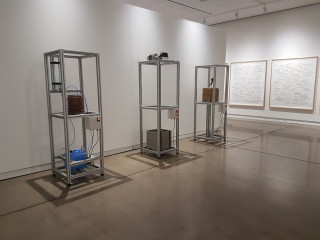

Group Show, On Display

Group Show, On Display

Artbank, Melbourne Projects Space, 2025

Group Show, Sanctuary: 25 Years of Hazelhurst Arts Centre

Group Show, Sanctuary: 25 Years of Hazelhurst Arts Centre

Hazelhurst Arts Centre, 2025

Group Show, Under the Big Blue Sky

Group Show, Under the Big Blue Sky

Casula Powerhouse, 2025

Group Show, Dreamz

Group Show, Dreamz

Sydney College of the Arts, 2025

Group Show, The Intelligence of Painting

Group Show, The Intelligence of Painting

Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia, 2025

Group Show, A Fictional Retrospective: Gertrude’s First Decade 1985–1995

Group Show, A Fictional Retrospective: Gertrude’s First Decade 1985–1995

Gertrude Contemporary, 2025

Group Show, Mnemosyne

Group Show, Mnemosyne

Museum of Contemporary Art, Australia, 2025

Group Show, Works on Paper

Group Show, Works on Paper

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024-25

Group Show, from elsewhere

Group Show, from elsewhere

Te Uru Waitakere Contemporary Gallery, 2024

Group Show, Suburban Sublime: Australian Photography

Group Show, Suburban Sublime: Australian Photography

QAGOMA, 2024-25

Group Show, Wilder Times: Arthur Boyd and the mid 1980s landscape

Group Show, Wilder Times: Arthur Boyd and the mid 1980s landscape

Bundanon Art Musuem, 2024

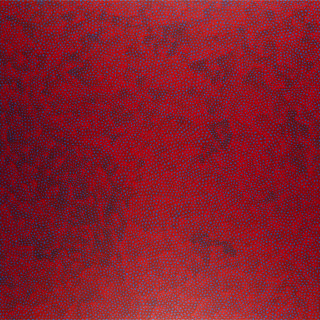

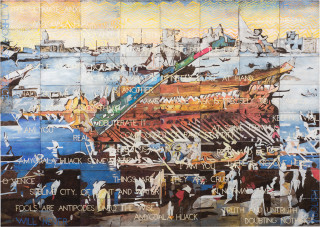

Ten Thousand Suns

Ten Thousand Suns

24th Biennale of Sydney, 2024

Group Show, What Does the Jukebox Dream Of?

Group Show, What Does the Jukebox Dream Of?

Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2024

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Group Show, The First 40 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2024

Group Show, The Winter Bride

Group Show, The Winter Bride

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2023

Group Show, Thin Skin

Monash University Museum of Art, Naarm/Melbourne, 2023

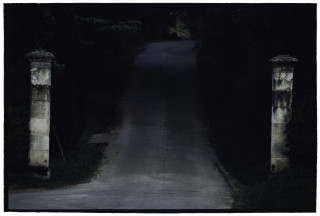

Group Show, nightshifts

Group Show, nightshifts

Buxton Contemporary, 2023

Group Show, The National 4

Group Show, The National 4

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney and Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2023

Thinking Historically in the Present

Thinking Historically in the Present

Sharjah Biennial 15, 2023

Group Show, Still Life

Group Show, Still Life

Buxton Contemporary, 2022

Group Show, Pliable Planes: Expanded Textiles & Fibre Practices

Group Show, Pliable Planes: Expanded Textiles & Fibre Practices

UNSW Galleries, 2022

Free/State

Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, 2022

Group Show, This language that is every stone

Group Show, This language that is every stone

Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2022

Cairns Indigenous Art Fair 2021, 2021

Cairns Indigenous Art Fair 2021, 2021

Group Show, The Great Invocation

Group Show, The Great Invocation

Garage Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2021

Group Show, The National

Group Show, The National

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 2021

Group Show, A Painting Show

Group Show, A Painting Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2020-21

Group Show, The Solar Line

Group Show, The Solar Line

NSW Visual Arts Emerging Fellowship, Artspace, Sydney, 2020

Viewing Room

Viewing Room

The Timbre of Texture, 2020

Viewing Room

Viewing Room

The Power of Language, 2020

Viewing Room

Viewing Room

Faraway, So Close!, 2020

Viewing Room

Viewing Room

Dreamscapes, 2020

Group Show, Contact Us

Group Show, Contact Us

Coment Fondu, Sydney, 2020

Group Show, Violent Salt

Group Show, Violent Salt

Artspace Mackay, QLD, 2019

Group Show, Idol Worship

Group Show, Idol Worship

Lismore Regional Gallery, NSW, 2019

Group Show, Mondspiel

Group Show, Mondspiel

Buxton Contemporary, Melbourne, 2019

Group Show, Caught Stealing

Group Show, Caught Stealing

National Art School, Sydney, 2019

Group Show, On Vulnerability and Doubt

Group Show, On Vulnerability and Doubt

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2019

Group Show, Workshop

Group Show, Workshop

University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2019

Group Show, Archibald Prize

Group Show, Archibald Prize

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2019

Group Show, Idols

Group Show, Idols

Fremantle Arts Centre, Fremantle, 2019

Group Show, Fringe

Group Show, Fringe

Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Belgium, 2019

Group Show, Just Not Australian

Group Show, Just Not Australian

Artspace, Sydney, 2019

Group Show, The Like Button

Group Show, The Like Button

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2018-19

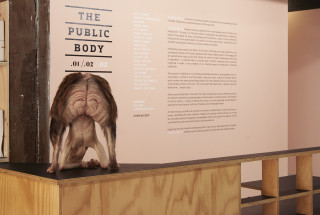

Group Show, THE PUBLIC BODY 0.3

Group Show, THE PUBLIC BODY 0.3

Artspace, Sydney, 2018

Group Show, The shape of things to come

Group Show, The shape of things to come

Buxton Contemporary, 2018

Divided Worlds

Divided Worlds

Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, 2018

Group Show, State of Play

Group Show, State of Play

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2017

Group Show, Future Eaters

Group Show, Future Eaters

Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2017

Group Show, Tidalectics

Group Show, Tidalectics

TBA21-Academy, Austria, 2017

Group Show, Looking at me through you

Group Show, Looking at me through you

Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, 2017

Group Show, Creative Accounting

Group Show, Creative Accounting

University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2016-17

Group Show, Sappers and Shrapnel

Group Show, Sappers and Shrapnel

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2016-17

Group Show, Soft Core

Group Show, Soft Core

Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, 2016

Group Show, Shut Up and Paint

Group Show, Shut Up and Paint

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2016-17

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2016

Group Show, Gravity (and Wonder)

Group Show, Gravity (and Wonder)

Penrith Regional Gallery, 2016

Group Show, Sixth Sense

Group Show, Sixth Sense

National Art School Gallery, Sydney, 2016

Endless Circulation

Endless Circulation

TarraWarra Biennial, 2016

Group Show, New Romance: Art and the Posthuman

Group Show, New Romance: Art and the Posthuman

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2016

Group Show, Wonder: Contemporary Art for Children

Group Show, Wonder: Contemporary Art for Children

Hazelhurst Arts Centre, 2016

The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed

The future is already here – it’s just not evenly distributed

20th Biennale of Sydney, 2016

Group Show, The Nest

Group Show, The Nest

Katonah Museum of Art, New York, 2016

Group Show, Dämmerschlaf

Group Show, Dämmerschlaf

Artspace, Sydney, 2016

Group Show, Really Useful Knowledge

Group Show, Really Useful Knowledge

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2015

Group Show, Dead Ringer

Group Show, Dead Ringer

Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, Perth, 2015

Group Show, People Like Us

Group Show, People Like Us

University of New South Wales Galleries, Sydney, 2015

Group Show, Solid State

Group Show, Solid State

Casula Powerhouse, 2015

Group Show, Light Show

Group Show, Light Show

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney, 2015

Group Show, Streetwise: Contemporary Print Culture

Group Show, Streetwise: Contemporary Print Culture

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2015

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2015

All the World's Futures

All the World's Futures

56th Venice Biennale, 2015

Group Show, Melbourne Noir

Group Show, Melbourne Noir

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2014-15

Group Show, Cars = my automolove

Group Show, Cars = my automolove

Caboolture Regional Art Gallery, 2014-15

Group Show, New South Wales Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging)

Group Show, New South Wales Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging)

Artspace, Sydney, 2014

Whisper in My Mask

Whisper in My Mask

TarraWarra Biennial, 2014

Group Show, The Gold Award

Rockhampton Art Gallery, Rockhampton, QLD, 2014

A Time for Dreams

A Time for Dreams

Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, 2014

Group Show, Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalists

Group Show, Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalists

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, 2014

Group Show, Never-Never Land (A Collaboration with Utopian Slumps)

Group Show, Never-Never Land (A Collaboration with Utopian Slumps)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2014

You Imagine What You Desire

You Imagine What You Desire

19th Biennale of Sydney, 2014

You Imagine What You Desire

You Imagine What You Desire

19th Biennale of Sydney, 2014

Group Show, Green Cathedral

Group Show, Green Cathedral

Wollongong Art Gallery, Wollongong, NSW, 2014

Group Show, Melbourne Now

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013-14

Group Show, Dawson, Griggs, Moore

Group Show, Dawson, Griggs, Moore

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2013

Group Show, Future Primitive

Group Show, Future Primitive

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2013-14

Group Show, History is Made at Night

Artspace, Sydney, 2013

Group Show, Ten Years of Things

Group Show, Ten Years of Things

UQ Art Museum, 2012-13

Group Show, Louise Bourgeois and Australian Artists

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 2012

Group Show, SEXES

Performance Space, Sydney, 2012

Group Show, Artists' Proof #1

Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne, 2012

Group Show, Cronies

Group Show, Cronies

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2012

Yayoi Kusama Eyes are Singing Out

Yayoi Kusama Eyes are Singing Out

Queen Elizabeth II Courts of Law, Brisbane, 2012-13

Group Show, Transit of Venus

Tin Sheds Gallery, Sydney, 2012

Group Show, The Other's Other

Artspace, Sydney, 2012

Group Show, MONA FOMA

Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, 2012

Group Show, Panto Collapsar

Group Show, Panto Collapsar

Project Arts Centre, Dublin, 2012

Group Show, Groups Who

Group Show, Groups Who

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2011-12

Group Show, Head On Photography Festival

Group Show, Head On Photography Festival

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2011

Group Show, Future Furnishing

Nature Morte Gallery, Berlin, 2011

Group Show, True Story

Group Show, True Story

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2010-11

Mikala Dwyer Mary's Place Lamp

Surry Hills, Sydney, 2010-13

Group Show, Wilderness: Balnaves Contemporary Painting

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2010

Group Show, Everything's Alright

Group Show, Everything's Alright

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2010

Group Show, Purlieu

Group Show, Purlieu

Awesome Arts Festival, Perth, 2010

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2009-10

Group Show, Grotto

The Fundament Foundation, Tilburg, The Netherlands, 2009

Group Show, Anne Landa Award

Art Gallery New South Wales, Sydney, 2009

Group Show, Lucky Town

Group Show, Lucky Town

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2008-09

Group Show, Process/journey

Australian Embassy and Redgate Gallery, Beijing, 2008

Group Show, Contemporary Australia: Optimism

Group Show, Contemporary Australia: Optimism

Gallery Of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2008

Group Show, OBLIVION PAVILION

Group Show, OBLIVION PAVILION

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2008

Group Show, ECR

Parramatta City Raceway, Sydney, 2008

Group Show, Oblivion Pavilion

Group Show, Oblivion Pavilion

Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, Melbourne, 2008

Group Show, Neo Goth - back in black

University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2008

Group Show, Dry Rot

Galerie Alexandra Saheb, Berlin, 2008

Group Show, Golden Mean

Casula Powerhouse, Sydney, 2008

Group Show, Summer '07 '08

Group Show, Summer '07 '08

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2007

Group Show, Views from Islands

Campbelltown Arts Centre, Sydney, 2007

Group Show, She's not Structural

Sydney College of the Arts, Sydney, 2007

Group Show, Increase Your Uncertainty

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, 2007

Group Show, STOLEN RITUAL

Group Show, STOLEN RITUAL

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2006-07

Group Show, Ten[d]ancy

Elizabeth Bay House, Sydney, 2006

Group Show, Adventures with Form in Space

Art Gallery Of New South Wales, Sydney, 2006

Group Show, Custom Living

Gallery Barry Keldoulis, Sydney, 2006

Group Show, Rectangular Ghost

Group Show, Rectangular Ghost

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2006

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2005

Group Show, When the Bulls Fight the Calves get Crushed

Siddhartha Gallery, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2005

Group Show, If these walls could talk

Group Show, If these walls could talk

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2005

Group Show, From Space to Place

IASKA, Kellerberrin, WA, 2004

Group Show, LOCAL +/OR GENERAL

New Canaan, Connecticut, 2003

Group Show, Z

Group Show, Z

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2003

Group Show, The Fly and The Mountain

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002

Group Show, Dirty Dozen

Group Show, Dirty Dozen

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2002

Group Show, IOU

Helen Lempriere National Sculpture Award, Melbourne, 2002

Group Show, The First 20 Years

Group Show, The First 20 Years

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2002

Group Show, Bittersweet

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2002

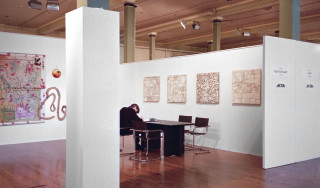

Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo, 2001

Group Show, All Stars

Group Show, All Stars

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2000

Group Show, more apt to be lost than got

Group Show, more apt to be lost than got

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 2000

Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo, 2000

Feria Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo, 2000

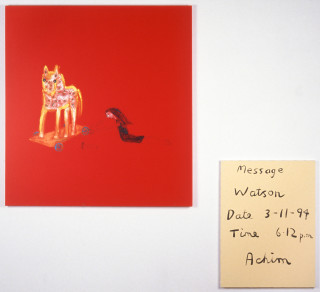

Group Show, Gang of Four

Group Show, Gang of Four

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1999

Group Show, Every other day

Group Show, Every other day

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1998

Group Show, Wish You Luck

Group Show, Wish You Luck

PS1 Contemporary Art Centre, New York, 1998

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1997

Group Show, A constructed world (in collaboration with John Wolseley)

Group Show, A constructed world (in collaboration with John Wolseley)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1997

Group Show, Give A Dog A Bone

Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1996

Group Show, Young British Artists

Group Show, Young British Artists

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1996

Group Show, Stockroom

Group Show, Stockroom

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1995

Group Show, Blow Up

Group Show, Blow Up

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1995

Group Show, Photosynthesis

Group Show, Photosynthesis

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1994

Group Show, Queerography

Group Show, Queerography

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1994

Group Show, 115 58' EAST 31 56' SOUTH

Group Show, 115 58' EAST 31 56' SOUTH

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1993

Group Show, High pop

Group Show, High pop

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1993

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1992

Group Show, T.I.S.E.A.

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1992

Untitled, 1992 - 1995

Online Gallery, 1992-95

Group Show, Abstract Art

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1992

Group Show, Christmas show

Group Show, Christmas show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1991

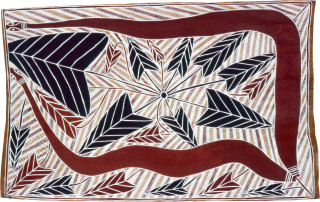

Group Show, Ramingining Bark Paintings and Sculpture

Group Show, Ramingining Bark Paintings and Sculpture

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1991

Group Show, Ramingining

Group Show, Ramingining

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1991

Group Show

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1990

Group Show, Strange harmony of contrasts

Group Show, Strange harmony of contrasts

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1990

Group Show, Recent Works from Ramingining and Maningrida

Group Show, Recent Works from Ramingining and Maningrida

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1989

Group Show, The Cocktail Party (All Gallery Artists)

Group Show, The Cocktail Party (All Gallery Artists)

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1988

Group Show, 7th Biennale of Sydney

Group Show, 7th Biennale of Sydney

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1988

Group Show, Mardi Gras exhibition

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1988

Group Show, 1968-1988 Selected works

Group Show, 1968-1988 Selected works

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1988

Group Show, Video Festival

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1987

Group Show, Chaos

Group Show, Chaos

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1987

Group Show, A Resistant Spirit

Group Show, A Resistant Spirit

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1986

Group Show, The Forbidden Object

Group Show, The Forbidden Object

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1986

Group Show, Yuletide nuptials fashion show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1985

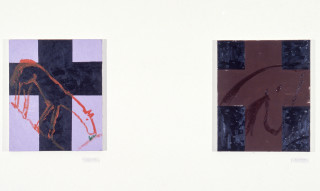

Group Show, Australian Visions

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1984

Group Show

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1984

Group Show, Dreams and Nightmares

Group Show, Dreams and Nightmares

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1984

Group Show, Young artists

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1983

Group Show, Pirates & Mutineers

Group Show, Pirates & Mutineers

Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, 1983